LeShawndra Price:

My name is LeShawndra Price, I'm Chief of the Health Inequities and Global Health branch

at the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. And I'd like to welcome you to the seventh

lecture of the Genomics and Health Disparities lecture series. This series is a part of an

ongoing dialogue about innovations in genomics research and technology can impact health

disparities. In addition to NHLBI the series is cosponsored by four other partners: The

National Human Genome Research Institute, the National Institute on Minority Health

and Health Disparities, the National Institute of Diabetes Digestive and Kidney Diseases,

and the Office of Minority Health at the Food and Drug Administration. Speakers have been

chosen by these five organizations to present their research on the ability of genomics

to improve health for all populations.

The speakers in the series approach the problem

from different areas of research, including basic science, population genomics, and translational,

and clinical research. We are honored today to have Doctor Herman

Taylor Jr. as our speaker. Doctor Taylor is an endowed professor and Director of the Cardiovascular

Research Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine and a nationally recognized cardiologist.

His current research predominantly focuses on preventive cardiology and his teaching

is aimed at building research capacity at minority serving institutions and enhancing

the health of minority communities through research and health activism at the community

level. Doctor Taylor may be most well-known for his leadership of the Jackson Heart Study,

the largest community based study of cardiovascular disease among African Americans, funded by

two of our sponsoring institutes today, NHLBI and NIMHD.

His extensive experience in epidemiological

observation has led him to a deeper appreciation of the urgency of community level intervention

as a priority as well as a keen interest in broadening the diversity of disciplines and

scientists focus on the problems of health disparities nationally and globally. A graduate

of Princeton University, Taylor earned his medical degree from Harvard Medical School,

trained in internal medicine at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, my alma

mater, and completed a cardiology fellowship at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Please help me welcome Doctor Herman Taylor. [applause] Herman Taylor:

Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen. It is a great pleasure to be here with you.

I'd

like to begin my remarks with a brief story. After leaving the Jackson Heart Study and

relocating to Atlanta and Morehouse School of Medicine, one of the first people I met

was a gentleman who somewhat aggressively called me and got me on the phone with — my

new assistant left him through by phone. And he said, "Doctor Taylor, you know I am interested

in your work I've followed your career and I'd like to hear more about some of the things

that you're interested in. Could I come over?" I said, "Why, certainly," and he made an appointment. So, the day came, and in walks this gentleman

he is grey haired and looked a little different than I expected from the vigor in his voice.

He handed me a sheet of paper, and it gave his most recent physical exam.

And it said

this man appears younger than his stated age. He is about 140 pounds, about 5'6". He has

normal vital signs and his physical exam is normal, although he does complain occasionally

of a little bit of hip pain. His labs were entirely normal, except for a creatinine of

1.3, and everything else was unremarkable. There was a clean bill of health. I looked

at the gentleman. I asked him how old he was. He said — I'll tell you later; that's the

punchline. But he cut the visit short because he had to be on his way. He had to go and

visit a friend of his who was his sergeant in World War II, who was ailing. This gentleman

was 92 years old, his friend was 101. Both of them were African American. Now, why do I tell you that story? I'll briefly

today just point out to you that heterogeneity is an important concept to keep in mind when

we're talking about African Americans and their health. There has been a huge and important

emphasis on disease and death as being excessive and premature among African Americans.

However,

there is — that is an incomplete story. I want to offer that we today briefly consider

three dimensions of health disparities: race, risk, and resilience. American raced based health disparities, as

you all know, are real, pervasive, and quite persistent. The last 30 years has given us

really a very important era and a deluge of literature that has outlined the — well,

given us the outlines of this problem, and made it indisputably a fact of how we view

American health.

Group comparisons are often the way that we dramatize the disparities.

They're useful, but they may contribute to a monolithically negative view of black health

and, I think, obscuring some opportunities. Black resilience is overlooked. And I believe

that's its study may offer fresh insights. This is a slide that all of the cardiologists

and cardiovascular research people are overly familiar with. That is that heart disease

is a problem. It is the number one killer. It has been so for a longtime despite the

fact that there has been a dramatic decline over the last half century in the deaths from

cardiovascular disease; some of that owing to possibly some of these landmark's labeling,

this annotation above and below this line showing the trend. I won't go into each of

these, but these are important advances along the way that Betsy Mabel and Eugene Braunwald

put together a few years back. Of course, that dramatic improvement in the public's

health with regard to cardiovascular disease has another side to it.

And that is the fact

that over that time, there has been an increasingly evident and discouraging disparity that's

emerged. Even though black and white have seen improvements the gap is there and widening. And all of this really led to an important

effort on the part of then HHS Secretary Heckler to call together a working group a task force

rather to put together this landmark report. I think most of you are probably familiar

with this. And it really did usher in an era of seminal discovery and publications that

again let the world know about the disparities in no uncertain terms. And that approach has

been again has been very, very, fruitful. It's taught us things about excess deaths

among blacks and other groups, access inequities of a variety of sorts, risk factor differences

that obtain in both groups, the potency, the great potency of social determinants of health. And a lot of this has led to the desire to

get more granular data on the underpinnings of a persistent epidemic among African Americans.

And I was pleased to be part of a major effort to get more granular detail on the African

American health experience with regards to heart disease and diseases of the circulation

called the Jackson Heart Study; a great idea to look in Framingham style at a population

of African Americans living in the deep south.

And to try to again get to the bottom of the

underpinnings of a persistent epidemic. Great idea, but not something that was easily accomplished. Just briefly about the Jackson Heart Study;

there was not overwhelming embrace of the study at first. As you can see, here are some

of the attitudes that we confronted when we began polling people back in 1998, before

the start of the study in 2000. During that two-year interim period, there were a lot

of meetings, a lot of interaction with the population, a lot of surveys, focus groups,

and the developing of an approach that is in large measure the community-based participatory

approach, which I think was in fact the key to us being able to pull the Jackson Heart

Study off. I mean, consider for a moment, Jackson is

what 200 plus miles from Tuskegee where some bad things happened that were in the memory

of the people that we wanted to be a part of this study.

And beyond that, in 1998 there

was new movie called Ms. Evers Boys, staring Laurence Fishburne and Alfie Woodard, that

dramatized this whole thing. That same year President Clinton apologized for Tuskegee.

So, Tuskegee was very much front of mind for black southerners who were being who were

being asked the question, we're here from the government essentially, and we want to

do a study just on black people. Are you ready for that? [laughter] So, it was something that we had to grapple,

with and thanks to a community that was in part motivated by the steady drumbeat of bad

news about black heath, it was their acceptance and building trust among them which was led

by our approach of involving them from the ground floor that led to the success of the

Jackson Heart Study; which as I think you know is still going forward today. Here are

some members of that community that we are forever grateful to. And granular indeed. So, we got a lot of information and we created

perhaps the most thoroughly phenotyped group of African Americans that you can find.

And

the Jackson Heart Study remains, this is a brief aside, very collaborative, and anxious

to work with people who are bringing good ideas for analysis of the comprehensive data

set. That's just one of the high-tech things that's available, that is MRI studies. Everything

from simple analysis and comparisons like obesity in Framingham versus Jackson, which

led to perhaps the not surprising observation that in stage II obesity, the prevalence is

three times as great among African Americans in Jackson as whites in Framingham and stage

I, there's double the prevalence. And only one-third of the population being in the normal

BMI in Jackson versus Framingham standard.

From those simple types of analysis to much

more complex opportunities that analyzed advanced variables, such as left ventricular stain

form MRI and a host of other things that I think are unique, unique in all of epidemiology.

All of this and more, there's not time to go in depth into the Jackson Heart Study and

its data base, but we are still, importantly I think, focused on risk. This is one of the

important recent papers to come out that talks about risk profiling, which represents again

a positive piece of progress in that novel biomarkers and subclinical disease measures

were employed to get a more refined prediction equation on the probability of an African

American developing a significant cardiovascular disease that came out of looking at a lot

of the variables out of the Jackson Heart Study.

But we still are looking at risk. And I think

looking at risk, again while valuable, misses an opportunity. So, group comparisons, when

you look at black versus white you keep getting these stories of white's up here, blacks down

here. But those comparisons obscure successes within the African American population. They

obscure stories like the gentleman I opened up the lecture with. And you know, obviously

that's anecdotal, but I challenge you to ask any person of African American descent about

this and whether or not they know people like this. We all do. A lot us see them in the

front row of church on Sunday morning. It is not an unusual phenomenon. Now, they themselves,

the 100-year old's and the vigorous 90-year old's, maybe outliers, but they're there and

they're there I think to teach us something. So, instead of thinking of blackness as badness

when it comes to health, note the facts. Yes, 50 percent of African Americans above the

age of 21 have hypertension. That's not good. That's bad. But 50 percent don't. And many

people suggest that given the stresses and strains of African American life that that

number might be higher.

You can imagine that, 85 percent of blacks don't have heart disease

while way too many do, a substantial number don't. And I think most of you are aware of

the interesting phenomenon that if blacks and whites reach an age of say 79 or 80, that

African Americans are at least as likely to live a long life and often outlive their white

counterpart's, contrary to prevailing notions of black infirmity. Resilience, I think, to use a word, is an

important idea that we need to look at in the African American context.

Health maintenance

in the face of risk that for some African Americans is overwhelming and contributes

to a deterioration in health and poor health statistics. But in others, is not the factor.

In fact, they overcome it and do well. Understanding the environmental individual promotors, promotors

of cardiovascular health within the black population is vastly under studied and I think

important for blacks, important for health disparities, but important beyond African

Americans. Because we have this ongoing 300 years, if you will, experiment in social marginalization,

deprivation, discrimination. These are facts of American history. We have that as a chronic

stressor, but despite that even today, there are African Americans who are 100 years old,

happy, and vigorous. What is the key to that? Now, resilience obviously is not a new idea.

It has its roots in medicine and social sciences in developmental psychology literature, where

it was noted, many years ago, that despite children having traumatic experiences, stressful

adversities in their youth, the phenomena of some of them not only maintaining and doing

well, but some of them truly thriving has been observed over and over.

That notion of

resilience is usually spoken of in terms, and measured, in terms like the ones you see

listed at these various levels. On the community level, social capital for instance, family

level, and social unit teamwork, reduce stigma. On the individual level, things like mastery

and even optimism. But, the phenomena of resilience are obviously noted in a variety of context.

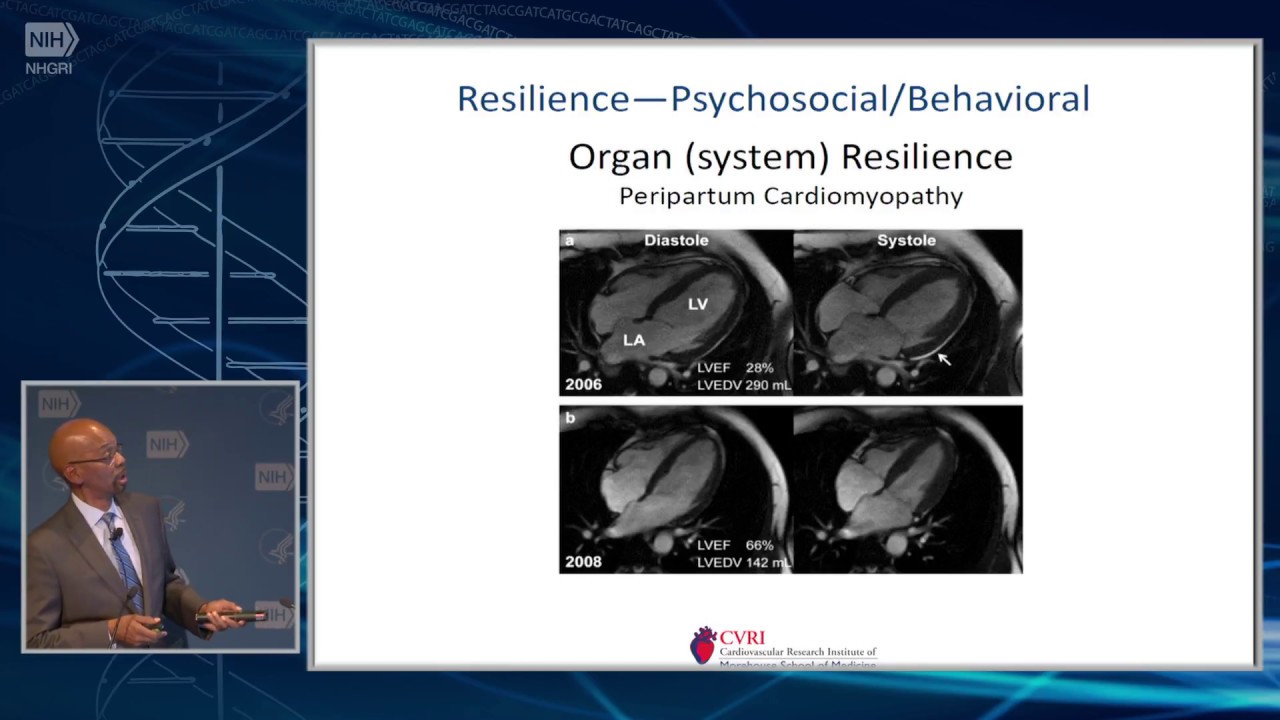

With a nod to Doctor Hannah Valentine, we see in diseases like peripartum cardiomyopathy,

you know, why is it that some of the women who go through that terrible ordeal actually

recover quite well — as in this case, a woman whose ejection faction dropped to 28 percent,

recovered to 66 percent — while others receiving similar care do not.

And they go onto heart

failure and heart transplantation. And even beneath the organ level the notion,

and this is taken from the toxicology literature, of cellular resilience. That is a cell exposed

to say the LD-50, that dose of a toxin that kills half the cells in a dish. Well, that

other half lives. What happened? What distinguishes one from the other? One population of cells

from the other? Here it's described in terms of starting with a baseline, a naive cell,

having the cell undergo a stress and in this model a toxin, sets the cell off on basically

one of two major pathways.

A pathway of defense, which could result in recovery and healing,

or even increased vigor, sort of increased toughness, for this cell. Robustness, it says

in this particular slide. Or a pathway of toxicity where the stressful event led to

negative epigenetic imprinting, let's say. And put the cell on a pathway of long term

adverse outcome or a much more immediate negative outcome. So, resilience on these levels, I

think, needs to be a thought, a consideration, a construct, that we embrace more fully.

Again,

the pattern, naive, stress, result. Now, our natural thought is well, you know,

if we just get rid of all risks, or study risks, and just reduce those, won't that result

in optimal health? Well, I think it's important for us to study risk and understand risk in

the African American population. But it's also important to understand that risk doesn't

tell us everything about the phenomena that we see, that we use, or that we understand,

to describe or characterize African American health particularly cardiovascular health. Here are just a couple of points. Factors

that should reduce risk often don't appear to in the literature. So, very often it's

noted that blacks don't receive the same cardiovascular benefits from a high social economics status,

that great equalizer in most folk's eyes, then whites. Social support has been noted

by my psychology colleagues as not always as protective as it appears in whites. Some

factors that should increase risk don't appear to. Some of the best outcomes in this study

around the South, led by Doctor George Rust, formally of Morehouse School of Medicine,

some of his best health outcomes were noted in the poorest of areas.

Contextual factors

that are protective in the North may be less protective in the South. There's all of this,

again, heterogeneity that we don't fully understand and, therefore, can't fully exploit. When we look at the sum total of the literature

we actually don't know a lot about the factors that promote resilience among blacks and that's

an important omission. We feel that Atlanta offers a particular good opportunity in terms

of exploring these problems. Because Atlanta is an example of an American city where there

is great heterogeneity among its population. I mean, we've got people who obviously are

down and out, even to the point of homelessness, and then you've got Tyler Perry and everybody

in between.

The point being that there's a lot of black affluence in Atlanta, there's

also black poverty, there's also a lot of other diversity in terms of immigrant populations

who are black. And there's a wide range as I'll show you in a second, of cardiovascular

health profiles that are represented in a place like Atlanta. Not that's it the only

place, but it's an ideal place.

And as a lot of you know it's been called the Black Mecca

of the South. Some D.C. natives might object to that. But that's what Ebony magazine says,

so it must be true. [laughter] And with an eye towards that opportunity we

formed something that we called MECA. And I teamed up with some colleagues at Emory,

and of course my colleagues in the Cardiovascular Research Institute, and across Morehouse School

of Medicine, to form the Morehouse Emory Cardiovascular Center for Health Equity.

Health equity as

I think most of you know is in the DNA of Morehouse School of Medicine and is what we

live and breathe there. And think back to that naive stress result model in disparities

research we posit that black race equals risk. Now, that sounds pretty dramatic when it's

just said as a standalone statement. But I think all of you would agree that you've read

paper after paper that has this in the conclusion or words like this. Independent of traditional

risk factors, African American individuals have a two to three times increased risk in

whatever is bad in that paper.

[laughter] All right. Even after adjusting for relevant

potentially confounding variables and so on. I mean, it's been a steady drumbeat, right?

So, black race equals risk in a lot of the literature that we read and consume every

single day. Well, we wanted to look at this idea of resilience

after the chronic or while being chronically exposed to those aspects of being black that

result in high risk and high cardiovascular risk in particular. And we're beginning to

look at not only sort of a global impression, but we're looking at three distinct levels.

The contextual level that is — and let me call it our Population Project where we're

looking at neighborhood context and using the best instruments available to us. That

will include an objective and a subjective assessment of the environment. Objective limited by the data we were able

to get form various data bases.

And subjective coming from this population of about 1500

people that we've interviewed by phone about this subjective experience of living where

they live; not in their county, but down to the census tract level so we get as much of

a microcosm of life as we can. And then, the individual level which actually has two levels

and we're calling these the Clinical and the Basic Projects. We're looking at psychosocial

and behavioral aspects through interviews and using standardized instrumentation to

assess these dimensions. And also, we're attempting to get a look at the vast epigenetic fingerprints

if you will of resilience. By looking at people who evidence resilience by our definition

and those who don't. Those who come from positive environments and those that are less positive. Okay, so, the aim of the first project, the

Population Project. Again, compare — we're trying to paint a picture. We're trying to

find those microenvironments that are particularly hazardous from a cardiovascular standpoint.

So, we're going to compare what we can; CV hospitalizations, emergency departments visits,

and deaths, among blacks across these communities across Atlanta.

And the second aim is to elucidate

factors that contribute to the community's cardiovascular resilience and risk at both

the census tract and eventually the individual level. And examine the relationships between

resilience and some of the standard risk factor scores. So, this what it looks like overall.

There are 940 census tracts, a lot of census tracts in Atlanta and we're going to try to

distinguish the at risk and resilient. That's the geographic spread. Atlanta — eventually

it's going to be all of north Georgia, but this is Atlanta right now. And in that red

we're going to again, look select census tracts that meet the criteria we want. Now, this is how it looked. These census tracts

with enough African Americans to allow the calculation of the rates that we use to determine

whether they are at risk or resilient.

And you know it's interesting to see that sometimes

they're right next door to each other the ones with bad CDV health statistics and the

ones with great CDV health statistics. So, we had these to choose from and what we did

was select those — we selected a subset of these census tracks that — a subset of about

214 — I'm sorry, 224 that, despite having similar highly similar median black incomes

— because we know SES and income is a powerful predictor of positive cardiovascular health.

But we wanted to take that out of the mix because I think we know the answer there in

the sense that income is irrefutability important. We wanted to know what else was operative.

And so, you see here median incomes that are very close, but, these census tracts had dramatically

different mortality rates in terms of cardiovascular disease. You see here nearly twofold dramatically

increased dependence on emergency department for healthcare. And the hospitalization rate

for cardiovascular diagnosis was dramatically higher in the at-risk population.

So, we're very early in the data collecting

and analysis, but this shows us that we can construct such a comparison. And the early

results from looking at the early data, suggest that census tracts across metro Atlanta have

variable rates of premature CVD. I think I showed you that pictorially. And this variation

exists even when median black household income is taken into account and we find both types

of tracts. Aim two was to look at maybe what in the context maybe related to these differences.

Okay. Now, admittedly we have to use somewhat blunt instruments to look at this. But I think

it begins to help us tell a story. So, with the population survey, which was 1500 people

that we did by phone with all of the challenges and limitations of that.

We were to gather

impressions subjectively of the neighborhood environments in these two types of communities

and we wanted to gather, through again, phone administered instruments, health, mental health,

health behavior, and social information, from the residents in the two types of tracts,

and of course, compare outcomes in both. And to sum up the early preliminary data on

this, again, intriguing, perhaps controversial, thought provoking. What has turned out to

be not significant in these particular tracts is the walking environment. The ability to

get out and walk to where you needed to go and exercise almost passively by doing so.

Activities with the neighbors, that whole idea of cohesion and community somehow being

healthful for cardiovascular health, was not evident in our data so far.

Okay. And I'm

caveating this heavily because it is early. And walkable grocery stores interestedly did

not fall out in early analysis as a significant community characteristic in terms of cardiovascular

health. In the people that did get on the phone with

us, there was a significant difference in global health in these different communities

where the median income was almost identical. All right. But you had this vast difference

in cardiovascular health parameters that we measured. We saw that their impressions of

their global health were distinctly better in the resilient neighborhoods. The evidence

of depression using standard epidemiological depressive symptoms scoring techniques there

was a significant difference and the more positive being in the resilient neighborhoods.

And levels of optimism were distinctly more evident in the resilient neighborhoods.

This

is just looking at the depression scores of percent using a cut point of 16 in a CSD.

Looking at the different percentages in and this was a significant difference. So, that's

where we are with the context. So, it's some interesting findings and again preliminary. Our next project, which is actually beginning

to run simultaneously, we're recruiting for this and enrolling in it now, is to look at

more individual characteristics.

Including looking at biomarkers of inflammation, such

as CRP, oxidative stress, regenerative capacity, vascular measures, noninvasive simple vascular

measures, to look at the condition if you will of the vasculature in these individuals

and whether there's subclinical disease that comes out as being more evident in people

of one context versus the other. And all of these markers will be adjusted for the Light

Simple Seven Score. So, we're going to again, look at, at risk

and resilient communities and march them through a protocol which will help us identify whether

or not they're individual characteristics that might be evident from people coming from

those environments. And this project flows into the next project three, which I'll show

you in a second, which looks at epigenetic and metabolomic parameters that may also be

flowing with the risk that people are experiencing either in their communities or at another

level, at an individual level that we don't fully assess until we get them into the clinic.

And these particular biomarkers were chosen

based on some preliminary work by members of our group that looked at that survival

after myocardial infarction. So, clearly survival here in red where the oxidative stress and

inflammation score was significantly higher was dramatically poorer for people who evidenced

high levels of oxidative stress and inflammation. Similarly, with low regenerative capacity

the post myocardial infarction mortality was significantly higher. And in an interesting

study we saw that neighborhood effects different neighborhoods actually if you drew blood and

looked at if from people who were in different types of neighborhoods, poor versus not so

poor, this is a different study. But what it showed was that you actually had different

levels of these inflammatory cytokines depending on neighborhood characteristics such as environment,

walkability, which seems to contrast with what I just told you from our current study,

and neighborhood cohesion. Again, that seems also to contradict that. But these were candidate

things to measure because of preliminary data from other studies.

And finally, we will take these people from

resilient and nonresilient environments and we'll randomize them into an intervention

which will be aimed specifically at altering their risks in more traditional risk factors.

So, we'll be aiming at things like blood pressure, cholesterol level, and so on, and physical

activity, with this intervention to see the before and the after. To see if there is any

change in any of the biomarkers that we have decided to investigate based on preliminary

data from other studies. And the basic project which is going to look

at again, beneath the cellular level, we will be looking at microRNA patterns that may be

tied to cardiovascular health or disease. We'll be taking the microRNA data, combining

it with metabolomic analyses done at Emory where Doctor Dean Jones has the capability

to measure over 20,000 chemicals in human serum.

That will give us insight into all

types of exposure and all types of metabolic activity. That information plus the microRNA

information will ideally give us some view on a subcellular level of who the resilient

people, again by our definition, are, who the nonresilient are, and whether or not a

change happens with intervention. So, this is admittedly very exploratory. A first step

in looking into the notion of resilience at a contextual level at an individual sort of

whole body level and a subcellular level. Some other studies that are going on in the

Cardiovascular Research Institute related to this same idea, include a very interesting

rat study that looks at a rat model for stress and PTSD.

And it's a very interesting idea

in that you take a rat, here, and you expose them repeatedly to a bigger more aggressive

species. All right. Over and over. And some of the rats will develop the rat equivalent

of PTSD, which is social avoidance. Now, the rat scientists may correct some of what say

here. But that is the basic idea. So, this is the aggressor and this mouse has

been traumatized by continual exposure to rats that are that size, that level of aggression,

over and over and over.

And when you put them — although this rat is caged you see a very

unnatural response from a very social animal. He's turned away and he's avoiding. Same exposures,

but this guy has not learned this behavior. Has not developed social avoidance and in

a way, has not developed the post traumatic distress that this one has. Our post doc Doctor

Chloe Gray is looking at what distinguishes these two mice on a molecular level and what

interventions might reduce the frequency of the development of this phenotype as a model

for addressing resilience with targeted therapy. We’re also looking at angiogenesis as a

mechanism of resilience. Already one of the microRNA's that has been isolated among African

Americans and whites derived from stored samples has been shown to incite if endothelial cells

over express that particular microRNA it's found that angiogenesis, a robust angiogenesis

is induced by the microRNA. Another one of our post docs is perusing that line of investigation

to see whether or not this could be a mechanism of a sort of resilience, particularly in the

context of diseases like myocardial infraction and heart failure.

And finally, another study to look at the

health disparities even before — with the idea being that we can look for indicators

of health disparities before they emerge by studying the young. We're looking at mobile

health cohort studies that will allow us to enroll young people. Right now, between the

ages of 18 and 29, in a study that will allow the gathering of granular real time and some

would suggest "in the wild" data. It doesn’t require people to come into a clinic for examination

or come into a hospital, but rather employ information on things like sleep, physical

activity, mental state, and other things, that can be obtained with the wearing of wearable

sensors to see what some of the early indicators of the emergence of disparities might be. So, what am I saying? Over the years even

before the Heckler Report, it's been observed by really even the most casual observer, but

among those of us who think deeply about social conditions and health, people like W. E. B.

Du Bois, it's been observed that the African American experience is quite unique and has

been for the better part of three centuries.

Here's his quote, "One thing we must of course

expect to find and that is a much higher death rate present among the negros than whites.

They have in the past lived under vastly different conditions and they still do." That was 1899.

I think this remains a fairly true statement. There have been of course — there have been

many advances. But I think if we were to freezeframe today that statement would not seem very radical

in 2017. What I'm inviting however is for us to embrace this notion of disparities and

continue to work on every possible front to resolve them. Social determinates of health,

making those less of an issue, access to care; all of those things have to be pounded on

continually. But I do want to introduce the notion that

if we look past the great successes within the African American population, people who

are living well today despite it all, people who have grown up through the teeth of some

of the worst conditions in terms of social inequities, people who were there for all

of those atrocities, all of those terrible things that happened in the 50's, 60's, who

are still with us; how do they do it? I mean, they're right in plain sight.

And I think

what they offer is a new way to think about what we can do in the present time to help

African Americans and others who suffer under the burden of health disparities. I think again, historically we've been here

focusing on unique vulnerabilities. A singular emphasis on risk and poor outcomes neglects

understanding of assets and positive aspects of black health. Recognition of heterogeneity

and resilience in the face of adversity I think promotes a complimentary and positive

pathway towards the resolution of health disparities. And frankly, I think your patients grow tired

of hearing nothing but bad news. They get a little weary of hearing that you know black

equated with negative or poor outcomes. Because that's not the whole story. I think as we talk to our students, and to

our patients, to our colleagues, about disparities and how blacks have had problems derived from

that I think we owe it to the black population, we owe it to our colleagues, and students,

and we owe it, I think, to the progress of science, to simultaneously acknowledge that

the general arc of blacks in North America has been one of survival.

That they have overcome,

in the words of the anthems of the 60's in many ways they have overcome, many, many of

them. And that's something worth studying and understanding. I'll close with this, how

many of you remember the song Spanish Harlem, "There's a rose in Spanish Harlem"? Anybody

old enough to? [laughter] No one will admit it. [laughter] Well, Ben Hill, the same guy who did “Stand

by Me,” and also Aretha Franklin later re-recorded it. And there's a line in that song that I

think is worth remembering. At the lyrical highlight of the song Ben says — well, it's

about a beautiful young lady who's living in the midst of poverty, and he says, "She's

growing up in the street/ Right through the concrete." I think it's important for us to

remember that for many African Americans life has been as hard as concrete, but they've

come through.

What is that trying to tell us a scientific community? These are not just

anecdotes, these are facts of life that demand explanation. And my challenge to you and to

me, is to understand this more deeply as a positive pathway towards resolving health

disparities. Thank you. [applause] Le Shawndra Price:

So, we have time for questions, if you will just proceed to the microphone on either side. Male Speaker:

Hi. Herman Taylor:

Hello. Male Speaker:

I enjoyed your talk. Herman Taylor:

Thank you. Male Speaker:

Did you look at the percentage of the population who were black in each of the census tracts,

and did that corollate with anything? Herman Taylor:

Yes. So, thank you for that question. We did. And in terms of — in most instances, the

higher the percentage of non-blacks in the population the higher the median income and

the more positive the parameters for cardiovascular disease. All right. Fewer hospitalizations,

fewer ED visits, et cetera. Again, you know we are still looking at that data, and I hope

I'll be invited back to give you a much more comprehensive review of it. [laughter] But your question is an important one, and

we're going to continue doing analysis on that.

Thank Male Speaker:

Thank you. Herman Taylor:

Yes? Tiffany Wiley:

Hi, Doctor Taylor. Herman Taylor:

Hello. Tiffany Wiley:

Tiffany Powell Wiley [spelled phonetically] from NHOBI. Herman Taylor:

It's good to see you. Tiffany Wiley:

You as well. It was an excellent talk very inspirational in thinking more about the way

we look more positively at the African American community. Just two quick questions. Do you

all look at perceived environment, in addition to built environment measures? And also, are

you looking at measures that look at experience across a life course to really get at what

those differences may be? Herman Taylor:

Right. Right. I mean, excellent questions. This is American Heart Association funding,

which is good. Its good money. But it only takes us so far. In terms of looking at the

subjective impressions, everything I showed you was self-report, at this point. And it

really does reflect how people view — the data I showed you today, really does reflect

how people view their environment. And we'll have to do more work in terms of what objective

things we can find out about it in terms of things like air pollution and those things

that are not so much subject to interpretation.

Tiffany Wiley:

Okay. And then, as far as life course measures, are you? Herman Taylor:

I think that's important. And I'm looking to the NIH to help us — [laughter] — expand our work into life course. Tiffany Wiley:

Okay. Herman Taylor:

The start of this mobile health cohort, which is essentially — the concept is an echo of

the Jackson Heart Study in that the idea is ultimately to take a ubiquitous platform like

the cell phone and use that as a means of data gathering. And to start as young as we

can. So, we're starting at 18 with this pilot where we hope to enroll our first cohort in

a big hack-a-thon, idea-a-thon party November 11. It's actually a lot more scientific then

I just expressed. [laughter] But we are gathering people soon for a pilot.

And with the help of sustainable funding we hope to see it grow.

And some day to scale

up to give us big data that we can use and hopefully follow people over a long period

of time. But in specific answer to your question, we have yet to look deep into the younger

ages or even prenatally. Tiffany Wiley:

Okay. Herman Taylor:

Thank you. Jerome Flegg:

All right, I did enjoy your talk as well. Jerome Flegg [spelled phonetically] from NHOBI.

There were a few social determinants of health that I didn't hear you discuss, marital status,

family cohesiveness, church going, and even educational level, which may not necessarily

equal income.

Herman Taylor:

Right. Jerome Flegg:

Are you looking at that? And are you finding differences in the resilient populations versus

those who are not? Herman Taylor:

Okay, so again, it's still early. So, the individuals what I gave you were data — let's

see I think I showed the slide of people self-reported their education. Did I show that? Jerome Flegg:

I don't think so. Herman Taylor:

Perhaps I didn't. Yes, in all of these communities, it was interesting the one's that we selected

as being comparable in income, but having differences in outcome. The percentage, this

is categorical stuff, the percentage of college-educated individuals is actually quite high. And particularly

it was even higher among the people who actually agreed to our interview. So, this is one of

the challenges of this type of research. So, you're getting often the best-case scenario

the people who sign up are not exactly like the people who are out there, okay. Jerome Flegg:

[laughs] That's true. Herman Taylor:

They are very rough approximations. It is a blunt instrument.

But it begins to set the

stage preliminarily for further studies. So, the point of your question is that more educated

less — I mean, more resilient. Jerome Flegg:

Yeah. I'm thinking also the family cohesiveness, the families that are together as opposed

to single parents. Herman Taylor:

Right, right. Jerome Flegg:

Church going. Things that don't necessarily equate to education probably are still quite

important. Herman Taylor:

Right. Right. And that's information that we can gather in the individual interviews

and we will do so. Jerome Flegg:

Thank you. Herman Taylor:

But I agree with you, very much that those types of things and the literature agrees

with you too, that those things matter a lot in terms of you know people's feelings about

their health overall, their mental conditions, their positive affect, and so on.

All of those

things are critical. Male Speaker:

Thank you. Herman Taylor:

Thank you, for your question. Doctor Valentine [spelled phonetically], so good to see you. Dr. Valentine:

Herman, good to see you, it's been wonderful. Thank you, for that outstanding talk. Could

you give us a little glimpse about what you're learning about the genetics and genomics of

health disparities from this wonderful cohort that's called the Jackson Heart Study? Herman Taylor:

Ah [laughs]. Dr. Valentine:

I know there's lots, but highlights. Herman Taylor:

And you know I wish we had one of the geneticists here to respond to that question. I think

you know some interesting things just to pull one thing out. And often the genetics of the

Jackson Heart Study winds up having its data pooled with other cohorts that are smaller.

So, we were talking earlier about sickle trait and things like kidney disease and coronary

disease. So, the data on kidney disease seems to be pretty strong that sickle trait does

predispose to a slightly higher risk of chronic kidney disease.

Particularly in the context

of blood pressure abnormalities and so forth. The data on coronary disease looks negative.

There's no increased risk, from what we see, of people having sickle trait as determined

by genomic analysis and the incidents and prevalence of coronary disease. The Jackson

Heart Study has participated in a lot of consortia that have had some major I think impact on

understanding of the you know of the human genome. Of revising some of the things that

we have taken for granted in terms of what the human genome consists of, of what other

earlier work has shown us and I think it will continue. But to give you the best answer

to your question, I need one of my geneticists to come and talk. Dr. Valentine:

Great, thank you very much. Herman Taylor:

Thank you. Calvin Troy:

Doctor Taylor thank you for the talk. Calvin Troy [spelled phonetically] from the National

Institute of Minority Health and Disparity. Herman Taylor:

Yes. Calvin Troy:

Interested in your research, in particular your analysis on the neighborhood characteristics. Herman Taylor:

Yes. Calvin Troy:

And I know that you matched the median household income of those neighborhood to select the

resilient and the at-risk neighborhood.

Will you be able to look at how the socioeconomic

precision of the participant relative to the median household income and see their health

outcome? Because I mean, your talk is about heterogeneity, even within the census tract

there may be heterogeneity in the socioeconomic position, which can predict their health outcome. Herman Taylor:

It's an important point. And the increased precision and other aspects of socioeconomic

position you know being able to make that case, a lot of that will depend on the subsequent

interviews that we do face to face. But your point is well taken. There is heterogeneity

and until we sort out some of those challenges in the contextual data we have to be fairly

reserved in our conclusions. I think we'll be able to see things a little bit more definitely,

again still quite — this is very exploratory, right. But we’ll have some more solid answers

when we look at issues of inflammation, oxidative stress, and some of the molecular parameters,

as we continue this study.

What I really want to emphasis is that we've

got to do this. You know the opening sort of salvo in this new effort to understand

resilience has to be taken. And I think what we're going to wind up at the end of this

study is with a whole bunch of questions. I think there will be very few answers. But

I think our questioning will be more precise and will set the stage for what we do next.

And I invite — I had my e-mail address on one of the slides.

Do we still have IT? I

invite these questions and they will be discussed in our meetings. So, I want to be sure that

if you have thoughts or questions about what was presented here or about anything in this

topic in general I really would like to hear from you. So, I'll just tell you it's HTaylor@msm

— [laughter] — as in Morehouse School of Medicine.edu.

[email protected]. And I'll I welcome your questions. You might put in the subject line "Lecture

Series" that would help me know what it's about. LeShawndra Price:

So, please join me in thanking Doctor Taylor. [applause] [end of transcript].